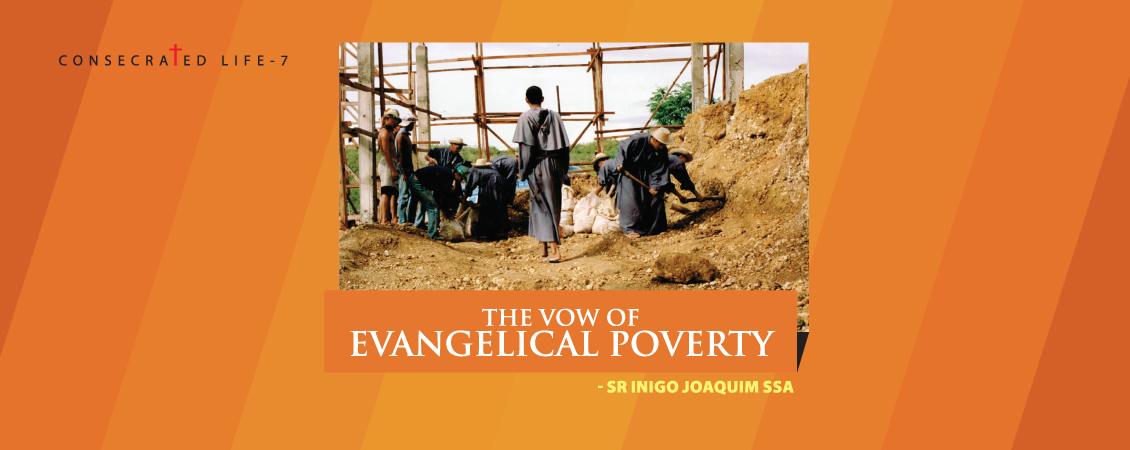

What does the vow of poverty mean today, in our context? Nobody wants poverty – neither material nor intellectual nor spiritual poverty. There is a global war going on for the eradication of poverty from the surface of the world, especially in the third world. Jesus never glorified poverty and misery. What does voluntary poverty mean when one has been forced to live in poverty all his or her life? What does poverty mean when one has more money or comfort in the religious community than in his or her family in the village? Is this the surest way of avoiding financial insecurity in a poor country like ours? As members of a financially secure institution, with good housing, above average levels of food, medical care, leisure, educational opportunity and social influence, we are not poor.

Our style of life has no more meaning and witnessing value in our country. Our wealth, comforts, power and position alienate us from the poor to whom we are called to be “Good News”. Our buildings with their compound walls, high gates and dogs, lawns and love birds and fish tanks; our expensive cars, excellent medical treatment when we need it and our mode of celebrations—all these are a counter-witness. After all, we claim to follow the poor man, Jesus of Nazareth. We are, of course, helping some poor people. But often they do not feel comfortable to approach us and we too find little time to be available to them in their needs.

We can speak of three different types of poverty:

A) Economic poverty: The poor are poor not because of their fault. Typhoons, droughts, floods, violence and wars destroy the poor. A little street girl asked Pope Francis in the Philippines, “Why does God allow such things to happen?” The response to economic poverty is to end it by hearing the cry of the poor and responding to it with sensitivity and generosity. Compassion is not enough. Just and effective structural measures are needed to combat economic poverty.

B) Sociological poverty: This kind of poverty exists because of selfishness and of exploiting and suppressing the weak by not paying a just salary or cheating the poor and silencing them. This is the case when we fail to pay just wages to our workers or we do not treat them with dignity and respect. The social dimension of religious poverty is to empathize with the poor and to alleviate their sufferings.

C) Spiritual poverty: This is what we call “Anawim” We do not have to be economically poor. In sickness and misery, we rely on God and surrender to Him. To be “poor in spirit” is to realize that we have nothing, we are nothing, and can do nothing by ourselves. Poverty of spirit is a consciousness of our emptiness. It is a sense of need and destitution. We are totally open to God. Sometimes we feel we cannot do anything. This is poverty of the spirit.

This vow places us on the way to defy materialism, consumerism and the justified ‘me’ism. Such a vow has less to do with ownership and more to do with stewardship. When people are dying of poverty, can religious professing to follow a man who was born poor, who lived and died in poverty afford the luxury of costly cars, a luxurious life-style, etc.? At the same time it does not mean that one should travel without reservation and enough money or to starve. Poverty need not mean misery, starvation and uncleanness in life, which of course are not virtues to be practiced but vices to be shunned. But the real meaning of poverty is sharing!

Sharing gives a totally different perspective. It is not a question of whether the other has it or not. The question is that we have got too much – we have to share. When we do charity, we expect the other to thank us. When we share, we thank him/her that s/he allowed us to pour out our energy – which was getting heavy; we feel grateful! And we need to see our giving not so much as charity but as obligation, as justice, as something we owe to the poor.

Asia or India is not poor. But there is an unequal distribution of resources. Hence we fight for peace, equality and justice. So we can call this vow as “Act justly” (Mic: 6:8) – a vow of stewardship, sharing and justice. We vow “to live simply” in a world overstuffed with commodities. Or, in an age of climate change, we respect the integrity of Planet Earth and “vow to live ecologically”. We live at the periphery, since poverty does not keep us at the centre of power. We choose to renounce power and prestige which material goods give, to be in solidarity with the poor. This vow will remind us of our duty to work for justice so that everybody will have enough to live a decent life.

All this requires an openness to the Spirit or, better said, a willingness to dance with the Spirit. Without an inner experience of joy in the Lord, it is unlikely that a person will choose poverty over riches or a simpler life over a life of luxury. Our life-style shows where our heart’s deep desires lie.Questions for Reflection & Sharing:

- Are we, members of religious orders, really poor?

- What does our vow of poverty really mean?

- Does our life-style put us among the rich, the upper middle class, the lower middle class or the poor?

- Would most people who deal with us consider us poor?

- The New Testament calls only one thing “the root of all evil.” That is: love of money. Does our life bear witness to a detachment from money and worldly goods?

- In what ways can we simplify our life, both collectively and personally?

- Some say that those who come from poor families are often the most attached to luxury. Have you found this to be true?

- By entering religious life, do most of us join a poorer and simpler way of life or a more secure and more comfortable life than at home?

- What inner attitude or spiritual experience would make a person want to lead a simple life?

- Have you personally experienced the joy of a simple life, of sharing, of being close to the poor?

To subscribe to the magazine Contact Us